Shays’ Rebellion: Disgruntled Farmers and the US Constitution

At the risk of oversimplification, the Declaration of Independence was kinda like a New Year’s resolution. Yeah, I can hear Thomas Jefferson vigorously spinning in his grave, but hear me out.

As cliché as they may be, New Year’s resolutions represent a conscious decision to make a positive change in a person’s life. Far too often though, either no real plan or a faulty one is set into motion leading to the equally clichéd broken New Year’s resolution. Likewise, the Declaration of Independence was a resolution; albeit one a bit more serious than losing those stubborn love handles. And, just like those New Year’s resolutions, it stood a high chance to fail and very nearly did.

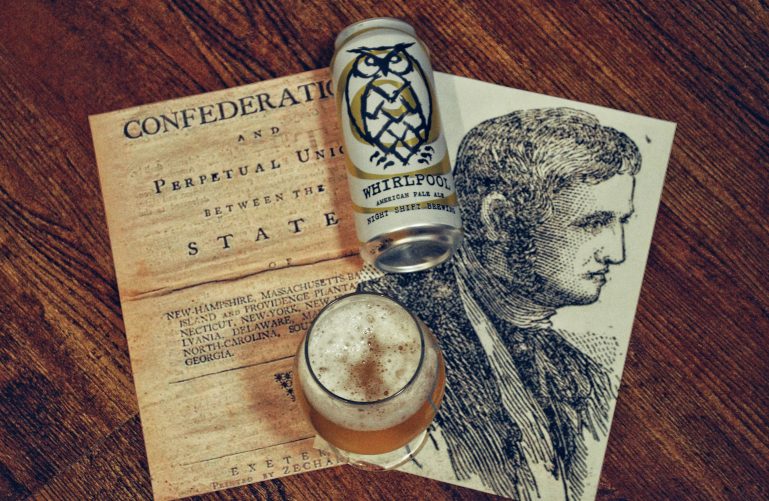

The Articles of Confederation

Now, I’m not talking about the patriots almost losing the Revolution, rather I’m referring to the five years between the Treaty of Paris and the ratification of the Constitution. During this period, the national government operated under the Articles of Confederation which served as the framework for the Continental Congress’ running of the patriot government during the Revolution. In a nutshell, all of the states would take care of all of their own affairs with a weak, centralized Congress that would resolve disputes between the states, make treaties, declare war, and coin money. Seeing as these guys just won their independence from a highly centralized government, you can’t really blame them for overcompensating in the opposite direction. So, without a strong federal government, the states governed autonomously, solving their own problems as they manifested. What could possibly go wrong?

Now, I’m not talking about the patriots almost losing the Revolution, rather I’m referring to the five years between the Treaty of Paris and the ratification of the Constitution. During this period, the national government operated under the Articles of Confederation which served as the framework for the Continental Congress’ running of the patriot government during the Revolution. In a nutshell, all of the states would take care of all of their own affairs with a weak, centralized Congress that would resolve disputes between the states, make treaties, declare war, and coin money. Seeing as these guys just won their independence from a highly centralized government, you can’t really blame them for overcompensating in the opposite direction. So, without a strong federal government, the states governed autonomously, solving their own problems as they manifested. What could possibly go wrong?

After the war, hard currency was in demand. While Congress could print money, it quickly depreciated because there was no specie to back it up. States could also print their own money, but some, like Massachusetts, refused to do so. Why? Quite often merchants and other prosperous city folk wielded the most power in the state assemblies and had no desire to diminish their own wealth. As merchants started calling in wartime debts, they demanded hard currency which your average farmer did not have. To add insult to injury, many of these farmers were former Continental Army soldiers owed money by the government for their service during the Revolution; money that the federal government couldn’t pay them because under the Articles of Confederation, they weren’t allowed enact taxes to pay its debts. What was the end result? Property and land were confiscated by debt collectors which left the farmer and his family with nothing except a strong feeling of being screwed.

These troubles were strongest felt in Massachusetts. By December of 1786, rural communities began to protest their treatment by interfering with tax collectors, returning confiscated property and eventually shutting down the various local courts that authorized the seizure of the debtors’ property. Instead of seeking compromise, Governor James Bowdoin and the Massachusetts Assembly quickly denounced the protests. Arrest warrants were issued for the ringleaders and the government even went so far as to suspend habeas corpus. These actions not only increased the protesters’ ranks, but also radicalized many of them. Now, instead of simply looking for debt relief, they began to plan for the overthrow of the Massachusetts government.

Daniel Shays: Rebel Ringleader

Daniel Shays served as one of the rebel leaders in the rebellion that would soon carry his name. Like many of his compatriots, Shays was a farmer in western Massachusetts and served in the Continental Army. Along with Luke Day and other leaders, Shays planned to attack the federal armory in Springfield to arm their rebellion. Aware of the Shays’ plans, the state government sent 800 militiamen under General William Shepard to defend the armory. After some miscommunication, only a portion of the rebels (around 1,500) approached the armory on January 25th, 1787. Some warning shots and cannon fire from the defenders quickly dispersed the Shays’ men who suffered 24 casualties (4 dead, 20 wounded) without firing a shot.

Fleeing to Petersham, the rebels were closely followed by General Benjamin Lincoln’s (no relation) merchant-funded militia. Surprising them on the morning of February 4th, Lincoln’s forces scattered the remaining rebels, many of whom, including Shays, fled to nearby New Hampshire and Vermont. The rebellion was over and Massachusetts soon offered amnesty to all participants if they swore loyalty to the state. Pretty anti-climactic huh?

The Impact of Shays’ Rebellion

While Shays’ Rebellion was a relatively minor affair, it helped convince many that a stronger federal government was a necessity. The federal government’s inability to raise taxes or regulate economic policy helped create the unrest that resulted in the rebellion. Additionally, despite the fact that the rebellion could have had nationwide consequences, the central government hadn’t been allowed to muster any troops in defense of the legally elected, albeit unpopular, state government. As it stood under the Articles of Confederation, future unrest and rebellion in any state could quickly spiral out of control. Disgruntled citizens could theoretically wrest control of a state and declare their own independence while everyone else watched. Sure, they’d still have their independence from Great Britain (which was after all the point of the Declaration of Independence), but how long could that independence be realistically maintained without working with each other? Thankfully, the ensuing Constitution Convention of 1787 helped solve many of those issues through the creation of the Constitution, keeping the United States intact as one independent nation.

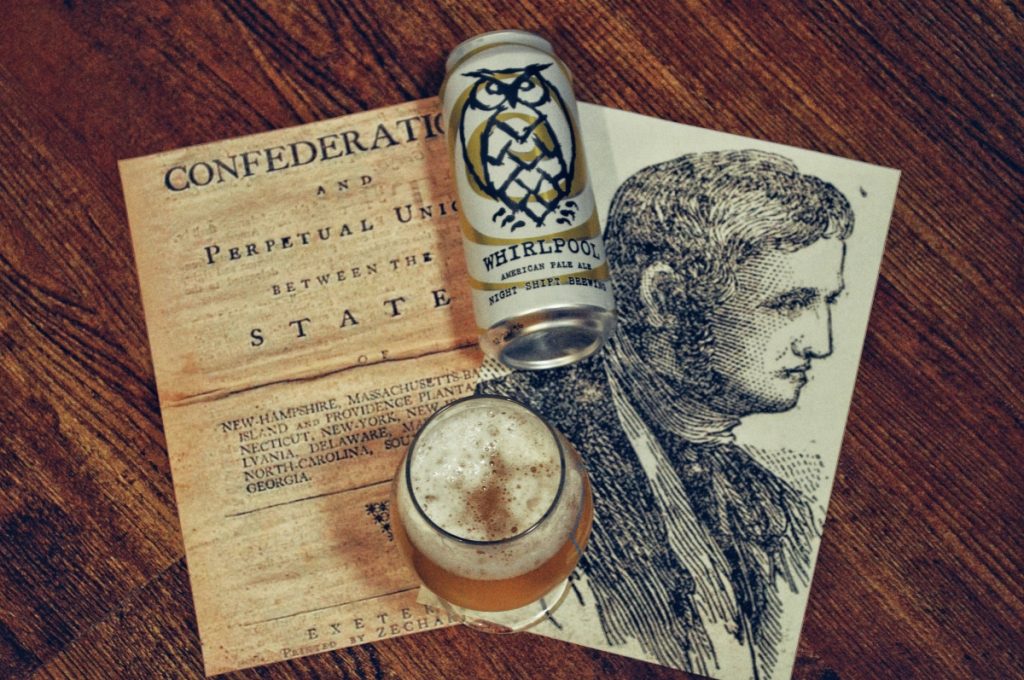

Craft Beer Pairing: Night Shift Brewing

Massachusetts’ role in early American history is undeniable and so is their role in their craft beer industry (I’ve already touched on both in a previous post). From Trillium and Tree House to Jack’s Abby, Harpoon and Samuel Adams, there’s no shortage of quality Massachusetts beer. Thankfully, all of it doesn’t require a trip to The Bay State and with Night Shift Brewing’s recent debut in New York City, there’s another option to add to my fridge.

Their trademark owl initially attracted me to Night Shift beers during a trip to Boston about two years ago. My dad had a tremendous collection of owl statues, so they hold a special place in my heart. Like many breweries these days, Night Shift’s normal rotation consists of hoppier offerings with a coffee porter (Awake), hefeweizen (Furth) and a pilsner (Pfaffenheck) thrown in for good measure. Their limited releases run the gamut from sours to different barrel-aged offerings and Belgian styles so they have an incredibly diverse portfolio. While I had an so-so visit last July (pushy bartender who seemed more interested in selling limited release bottles than anything else), I’ve yet to be disappointed with any of their beer. Their low-key arrival in the crowded NYC market was a pleasant surprise and hopefully we’ll be getting more of their stuff in the future.

Whirlpool, a very sessionable American Pale Ale at 4.5%, strikes me as a perfect beer for warmer weather. Pouring a cloudy, straw yellow, you’re hit with a strong lemon cracker aroma. The dense white head sticks around for awhile, making the possibility of a foamstache almost a certainty. Packed with Mosaic hops, there’s ton of lemon, herbal and tropical notes to complement the light bready malts. Light bodied, crisp and refreshing, there’s almost no bitterness making it an absolute joy to drink. Good enough to break a resolution over? I’ll leave that decision up to you, just be thankful that resolutions aren’t always meant to be broken.

2 Comments