Bitter Ales: The Relativity of Beer Styles

Bitterness is polarizing. So why would anyone who isn’t obsessed with bracing flavors ever want to drink a beer dubbed a bitter? Because sometimes names can be deceiving.

Some people love the bite of broccoli rabe or the zest of a bold West Coast IPA. Others would rather lick a shoe. Considering our ability to taste bitterness developed as an early warning sign to poison, can you blame them? Note to self: Write a murder mystery involving poisoning unsuspected IBU junkies with strychnine.

So, where do classic English bitters fall on the bitterness scale for modern American craft beer drinkers? Pretty meh. Your average American Amber Ale, like New Belgium’s ‘Fat Tire’ or Maine Beer Co.’s ‘Zoe,’ will have more bite. What gives with the name then? False advertising? Super tasters naming styles? Let’s hop back to Ye Olde England and find out!

Pale Ales: A Bitter Proposition

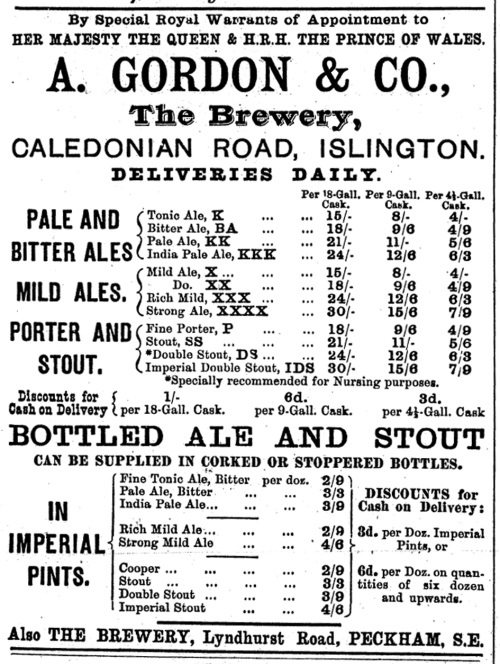

Changes in kiln design and fuel sources allowed British maltsters to create consistent pale malt by the end of the 1600s. Specifically, the use of coke (of coal byproduct fame, not soda secret ingredient infamy) meant less smokey flavors and more (controlled) variety in malt colors. Combined with the growing use of hydrometers, these innovations helped brewers realize that brewing with pale malts was more efficient than previous methods. Brew the same beer with more consistency for less money? Sign them up!

All manner of dark beers hung around, but pale ales rose in popularity throughout the 1700s. Keep in mind, however, that the term pale was relative. These pints were pale compared to a porter or a brown ale, but to our discerning eyes, they’d be in the amber to copper range. Golden lagers were still about a century away.

As it turns out, bitter was a relative term as well. This new subdued malt allowed the flavors of other ingredients to shine in brews. One of those newly accentuated flavors happened to be bitterness from the hops. As a result, in order to distinguish them from porters or sweetish milds, pubflys dubbed these new beers bitters. The name stuck and brewers began advertising them using the same moniker. Were they as bitter as a Dogfish Head ‘90 Minute IPA’ or even a Sierra Nevada ‘Pale Ale’? Nope, but to drinkers unaccustomed to wrecking their palates with the hoppiest thing they can find, they definitely were.

Pale Ales vs. Bitters

British drinkers and brewers used the terms “pale ales” and “bitters” interchangeably for decades. In fact, there’s a bit of debate about when they split into unique styles. Nowadays, bitters have a lower alcohol percentage, less bitterness and more malt character than your average pale ale. In other words, picture everything you’ve ever heard of a stereotypical English beer and it would probably be the spitting image of a bitter.

Fittingly, bitters are the beer of choice for the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) Movement in England. Much like the American Craft Movement, CAMRA was founded to fight against the homogenization of the beer industry. They’re infamous sticklers about their prefered serving methods (think room temperature wooden casks), but they’ve done an incredible job at keeping British brewing history alive.

Bitter Categories

Bitters are broken into a few varieties based on their alcohol percentage. Before our modern obsession with styles, many beers were simply lower alcohol versions of the same brew. Brewers might call batches with the lowest ABV “X” Ales. More alcohol? Throw another X on there. Of course, there were variations, like the Scottish ‘Schilling Scale’ or the Bitter ‘SOB Scale.’ Yeah, I kinda made that last one up, but it’s just so fitting.

In essence:

- Ordinary (Standard) Bitters: 3.2-3.8%

- Best (Special) Bitters: 3.8-4.6%

- Strong Bitters: 4.6-6.2%

Where does the popular ESB fit in this picture? Fuller’s Brewery in London trademarked the term Extra Special Bitter (ESB) in 1988. They began brewing a strong ale in the 1970s and to make it stand out from their special bitter, London’s Pride, Fuller’s dubbed the beer Extra Special Bitter. Their ESB became wildly popular so they decided to protect its name. Outside of England, however, anyone can call their beer an ESB and it’s simply become the style name of choice for American craft breweries.

TL;DR Bitter Breakdown

Historically, bitters are English pale ales that originated with the widespread adoption of pale malt in the late 17th to early 18th centuries. Despite their name, modern variations are all about balance between sweetness from the malts and bitterness from the hops. Pouring anywhere in the gold to dark copper range, bitters display hints of caramel and sweet malts along with earthy, piney, herbal or floral hops, and fruity English yeast characteristics. Strong bitters (ESB is a trademarked term) have the highest alcohol percentage (around 4.6-6.2%) of the various modern bitter variations being brewed. English pubs often serve bitters on cask and they’re best served at warmer temperatures (around 50-55 degrees).

Bring on the Craft Beer!

Tree House Brewing brews A LOT of New England IPAs. Like any good brewery though, they play around with different styles. Their ‘Old Man’ is not only a tribute to a classic style, but also an homage to head brewer Nate Lanier’s father, Dan.

A dark copper pour, ‘Old Man’ offers aromas of toast, caramel and nuttiness. The first sips echo the nose with the additions of earthy and faint citrus qualities. Medium bodied, but smooth, ‘Old Man’ finishes moderately dry with touches of bitterness. Great version of a historical treat!

‘Old Man’ Specifics

Brewery: Tree House Brewing

Location: Charlton, MA

Style: Extra Special Bitter

ABV: 5.4%

Notable Ingredients: Fuggles hops

Release Notes: Rotating release