The Newburgh Conspiracy and George Washington’s glasses

The British surrender at Yorktown on October 19th, 1781 marked the end of the American Revolution even though the Treaty of Paris wouldn’t be signed until almost two years later.

Hostilities halted (except for a few minor engagements), but the British maintained control over New York City, Charleston (until December 1862) and some minor outposts in the Ohio River Valley. Their continued presence meant that the Continental Army needed to remain intact in case the dastardly redcoats tried some funny business. Ironically, the greatest threat to the fledgling republic during this period came in early 1783 from the Army created to protect the United States and not a foreign power. Dun-dun-duuuuuuuuuuuun.

The State of the Continental Army

The Continental Army dealt with a lot during the Revolution. Even when they weren’t being outmaneuvered by the British, they continually suffered from a lack of supplies and money. While the conclusion of the horrible winter at Valley Forge represented a turning point in some respects, it was a constant struggle to obtain necessary resources from the Continental Congress.

As you may recall from a previous post, the national government under the Articles of Confederation was incredibly weak. While they could maintain a standing army, Congress could not demand money from the states to help pay for its maintenance. You’d think that the states would happily provide funds to assist the soldiers who fought and died to create their new republic, but that wasn’t the case. Officers and soldiers were sporadically paid, if at all, and quite often the army had to seize, or use their own money to purchase, supplies from citizens.

Complicating matters even further, Congress had passed resolutions promising additional salary to officers after the war ended, as well as enlistment bonuses to the soldiers. It had the intended effect of increasing the size of the army, but eventually reality kicked in. Now that the war was nearly over, it looked incredibly unlikely that the Congress would ever be able to keep those promises. Many soldiers had seen their personal affairs fall into disarray while they were serving, making the threat of losing money that could help their families rebuild an incredibly bitter pill to swallow.

Once they no longer had to worry about getting shot at or decapitated by a cannonball, many soldiers began to reflect on the situation. Feeling disrespected, angry and increasingly hopeless, many saw the coercion of Congress as their only solution. In December of 1782, Major General Henry Knox and a number of officers sent a petition to Congress asking them to find a remedy to the situation. They warned that “[t]he uneasiness of the soldiers, for want of pay, is great and dangerous; any further experiments on their patience may have fatal effects. . .they [the officers] therefore entreat, that Congress, to convince the army and the world that the independence of American shall not be placed on the ruin of any particular class of her citizens, will point out a mode for immediate redress.” Congress’ response? Nothing.

Are you ready for all of this to get even more interesting and a bit more complicated? Great! Me too!

Congressional Conspiratorial Collusion

A number of delegates in the Continental Congress realized that the United States needed a stronger national government if they hoped to survive. In 1782, Alexander Hamilton, Robert Morris and Gouverneur Morris (who unfortunately was never actually a governor) argued for an amendment to the Articles that would allow the national government to raise revenue through taxes. Time and again, however, their arguments for strengthening the government fell on deaf ears. The majority of Congress still insisted that state governments should have the most power and any centralized authority must be kept weak in order to prevent the creation of another authoritarian government. What could possibly change the minds of these delegates? How about the threat of a coup d’etat by the Continental Army? Yes, folks, the majority of the Founding Fathers were just as ruthless as modern politicians and don’t let anyone tell you any different.

A number of delegates in the Continental Congress realized that the United States needed a stronger national government if they hoped to survive. In 1782, Alexander Hamilton, Robert Morris and Gouverneur Morris (who unfortunately was never actually a governor) argued for an amendment to the Articles that would allow the national government to raise revenue through taxes. Time and again, however, their arguments for strengthening the government fell on deaf ears. The majority of Congress still insisted that state governments should have the most power and any centralized authority must be kept weak in order to prevent the creation of another authoritarian government. What could possibly change the minds of these delegates? How about the threat of a coup d’etat by the Continental Army? Yes, folks, the majority of the Founding Fathers were just as ruthless as modern politicians and don’t let anyone tell you any different.

A few quick words before I continue. First, some parts of the conspiracy are conjecture. While most historians will agree that the actions of certain members of the Continental Army were pushed by certain members of Congress, there is not a ton of concrete proof. I mean, would you leave around letters talking about plotting the attempted overthrow of the government?

Second, the nationalists (delegates who supported a stronger national government) did not actually want the coup to happen; they simply wanted the threat of it to scare members of Congress into agreeing to the creation of stronger central government. In a letter to George Washington in February of 1783, Hamilton subtly warns of the impending unrest: “The great desideratum at present is the establishment of general funds, which alone can do justice to the Creditors of the United States (of whom the army forms the most meritorious class), restore public credit and supply the future wants of the government. This is the object of all men of sense; in this the influence of the army, properly directed [boldface mine], may cooperate.” Kinda treasonous? Hell yeah. Kinda necessary? Probably.

Plotting a Coup in Newburgh

The bulk of the Continentals were camped in Newburgh, around 60 miles from New York City, so the nationalists looked there for an officer to fan the flames of discontent. Washington was out of the question, because he was, after all, George freaking Washington, savior of the American republic. Knox, the co-author of the Army’s grievances sent to Congress, seemed to be a good fit, but he was entirely too loyal to Washington. General Horatio Gates, second in command at Newburgh and noted foe of Washington wound up doing just nicely.

On March 10th, a letter circulated Newburgh from an anonymous source (who later turned out to be Major John Armstrong Jr., aide to Gates). Lamenting Congress’ unwillingness to listen to their pleas and stoking the fears that the soldiers would eventually die penniless, Armstrong noted that they have two options: “If [the war ends], that nothing shall seperate them from your Arms but Death—If War [continues]—that courting the Auspicies, and inviting the direction of your Illustrous Leader, you will retire to some unsettled Country.” In other words, abandon the war if it continues or refuse to disband if it ends. The implication from the latter isn’t that they’ll just hang around and sing Kumbaya. Rather, they’ll march to Philadelphia to force Congress to pay. And if Congress couldn’t pay, perhaps a new government could.

A secondary notice worked its way through Newburgh calling the officers together for a meeting to discuss their options. To put it lightly, Washington was not happy. He knew it was his duty to “rescue them from plunging themselves into a gulph of Civil horror from which there might be no receding. . .” In his General Orders for March 11th, Washington noted “his disapprobation of such disorderly proceedings.” He did however, ask that the officers meet on March 15th to further discuss the measures in hopes that they would agree to measures that were the “most rational and best calculated to attain the just and important object in view.” Rather cunningly, he implied that he wouldn’t be attending the meeting himself. Old George had set them up and now it was time to knock them down.

George Washington and the Original Masterclass In Tact

The officers, with Gates presiding, met on March 15th. Much to the surprise of all present, Washington walked in as the meeting began and asked to speak. In a speech that condemned the implied threat of a coup and denounced the cowardice of the anonymous ringleaders, Washington urged the officers to remain patient and trust that he would do everything within his power to lawfully address their grievances. By firmly denouncing “the Man who wishes. . . to overturn the liberties of our Country, & who wickedly attempts to open the flood Gates of Civil discord, & deluge our rising Empire in Blood. . .[they would] afford occasion for Posterity to say, when speaking of the glorious example you have exhibited to man kind, “had this day been wanting, the World had never seen the last stage of perfection to which human nature is capable of attaining.” Say what you will about his teeth, this guy could talk.

Many of the officers, however, seemed to still be unconvinced. Knowing that sometimes it’s best for the participants to speak for themselves, I’ll let Major Samuel Shaw describe what happened next:

“After he concluded his [Washington’s] address, he said, that, as a corroborating testimony of the good disposition in Congress towards the army, he would communicate to them a letter received from a worthy member of that body, and one who on all occasions had ever approved himself their fast friend. . .His Excellency, after reading the first paragraph, made a short pause, took out his spectacles [which only a few had ever seen him wear], and begged the indulgence of his audience while he put them on, observing at the same time, that he had grown gray in their service, and now found himself going blind. There was something so natural, so unaffected in this appeal, as rendered it superior to the most studied oratory; it forced its way to the heart, and you might see sensibility moisten every eye.”

To quote the Ghost of Christmas Past from Scrooged, “Niagara Falls, Frankie Angel.”

Whether or not this was a carefully scripted act by Washington, the simple act of putting on a pair of glasses effectively stopped the Newburgh Conspiracy in its tracks. The action reminded the officers that Washington had suffered along with them throughout their struggle against Great Britain. Washington could easily be the one leading them to force payment from Congress and yet here he was urging patience and moderation in order to save the republic that they had helped create.

True to his word, Washington continued to petition Congress as well as members of the state governments to help resolve the issue of compensation. Showing his deeper understanding of the whole affair, he also warned his protege Hamilton that Congress should be careful about manipulating the Army to further their goals because “the Army. . .is a dangerous instrument to play with.” When all was said and done, Congress agreed to give all officers a payment equal to five years salary in order to satisfy their claims. However, Congress would still remain powerless in their attempts to collect this money; a problem that wouldn’t be solved until the adoption of the Constitution six years later.

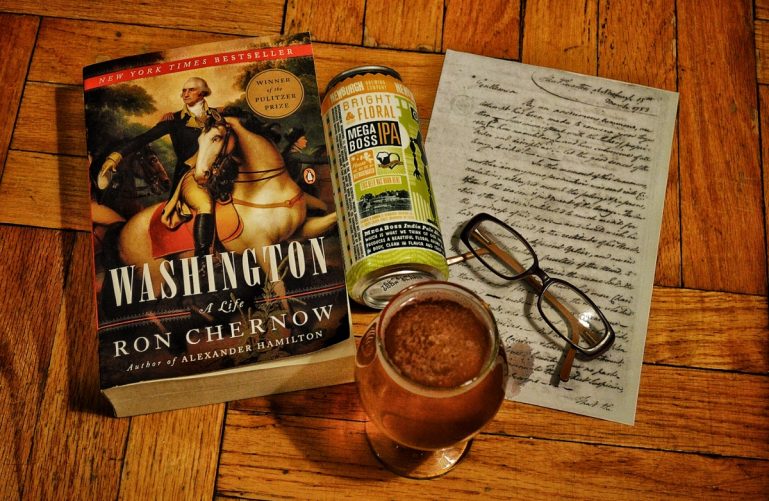

Beer Pairing: Newburgh Brewing

Located in the former stomping grounds of the Continental Army, the aptly named Newburgh Brewing opened in 2012 and operates out of a restored mill that overlooks the Hudson River. The brewmaster, Chris Basso, brewed under Garrett Oliver at Brooklyn Brewery before enlisting the help of his high school friend, Paul Halayko, to open up their own brewery. While the city of Newburgh has seen its fair share of hard times in recent history, Halayko and Basso chose it for its convenient location (I-84, the NYS Thruway and the Beacon Metro-North Station are all nearby), gorgeous buildings and their desire to help revitalize the area, which, as Halayko points out, “has a rich amazing history and was once considered one of the best places to live.”

Awarded best taproom in New York by ratebeer.com, Newburgh offers a wide variety of seasonal and rotating beers (including a Russian Imperial Stout named after The Newburgh Conspiracy!) to complement their core lineup. Their bestselling beer is their award winning Cream Ale, an oft forgotten style that holds an important place in New York State history.

Unable to get my hands on a bottle of The Newburgh Conspiracy, I, rather predicably, took the hoppier path with a can of their MegaBoss IPA. The “middle” of their hoppy offerings between GigaBoss Double IPA and NanoBoss Session Pale Ale, MegaBoss and its 8 (!) different hop varieties promises “a rich pineapple and tropical fruit aroma, with a flavor profile that very much follows that aromatic start, concluding with a lemon and herbal hop finish.” Does it live up to such lofty expectations? Unlike the Continental Congress, yes it does.

Hazy golden with a quickly disappearing white head, MegaBoss looks like your run of the mill IPA. Cracker malts, grass, lemon and pineapple blend together to create an incredibly refreshing aroma. Not researching the beer beforehand, the first sip put a smile on my face. Why? The unmistakable flavor of Sorachi Ace! There’s a fantastic herbal, lemongrass quality that makes me feel like I’m out in a field. Except for some cracker malts and sweet citrus, the Sorachi Ace definitely takes center stage in this beer. Super bold move because it can be a bit of a polarizing hop. Combined with mild bitterness, medium body and lively carbonation, it makes for a super refreshing and easy to drink beer that offers a lot of flavor not found in many IPAs.

Why the Continentals didn’t think of starting a brewery to pass their time in Newburgh instead of plotting the overthrow of the American government is beyond me. Regardless, let’s raise a glass to George Washington’s glasses and be thankful that his myopia didn’t cloud his vision of America’s future. Cheers!

1 Comment